Goodmon does not want to be the last Black man in Leimert Park (or South L.A.), so he’s looking for community members to join the fight against gentrification.

By Jason Lewis

Damien Goodmon lives in Leimert Park, and he walks to the Umoja Center on 43rd Street, right off of Degnan Boulevard. He walks through a predominantly Black neighborhood and past predominantly Black-own businesses, but the demographics have been changing over the last couple of decades, as gentrification is taking place in many Black neighborhoods in South Los Angeles.

Black neighborhoods in South Los Angeles are getting a facelift with Metro’s Crenshaw/LAX line, luxury apartments, and brand new amenities. But as the community is finally being fixed up, many of the long time residents may not be able to afford to stick around and benefit from the improvements.

“For the people who have been in these communities during challenging times, don’t they have a right to enjoy the additional transit options that are coming to them?” Goodmon asked. “Don’t they have a right to enjoy and participate in the additional economic activity that’s coming to this area? How messed up is it to tell the bulk of us who are low income, now that stuff is getting good, it’s time for you to move to Victorville so other folks can enjoy this. Thank you, but you’re banned to the desert; your Black reservation.”

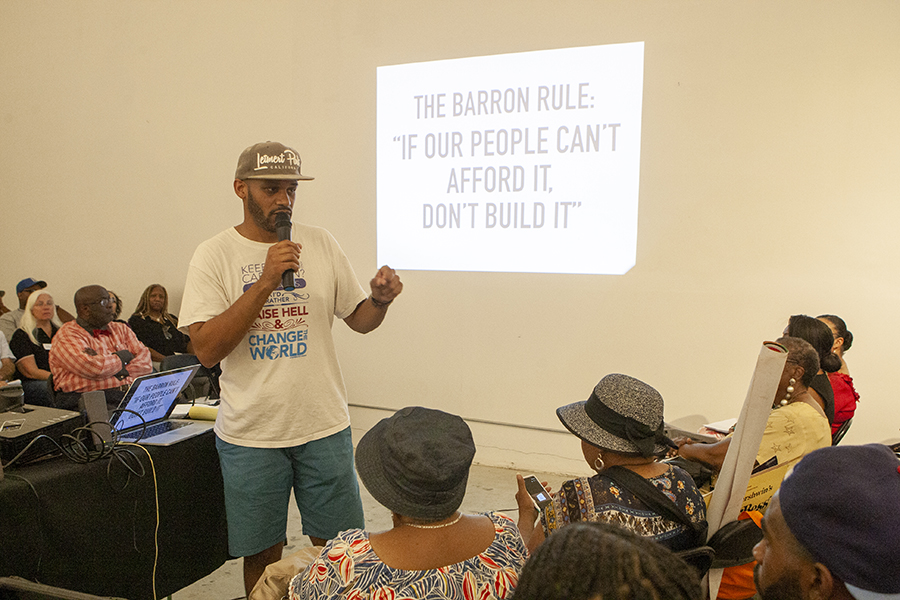

Goodmon, who is the Executive Director of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition, isn’t just talking about the issues surrounding gentrification; he’s doing something about it. This past September he hosted a series of town hall meetings at the Umoja Center to educate community members on policies and developments that will affect their ability to continue to live in South Los Angeles.

“We engaged in what we call the Summer of Resistance Town Halls on Gentrification,” he said. “It was our first public and ongoing meetings in the Umoja Center. It was to highlight some of the largest projects and policies that are fueling gentrification within the community today and are opposed to our future.”

These meetings focused on three objectives surrounding the development along the Crenshaw corridor. The town hall meetings informed the public about the developments and how those projects impacted community members; gave people an opportunity to take action against gentrification; and encouraged people to join the Crenshaw Subway Coalition’s efforts to combat gentrification.

Goodman founded the Crenshaw Subway Coalition in 2006 with the intent to be involved in land use issues. The objective is to ensure that the economic development along the Crenshaw corridor would be community driven and based on principles of local economic empowerment. Goodmon emphasizes the use of the phrase “economic empowerment” opposed to “economic development.”

“There’s a traditional method of engaging in so-called community economic development when really the objective is simply to at best bring in a Black face to make a few million dollars while still providing poverty level wages and inadequate access to provide economic mobility for people who live in the community,” he said. “There are several examples of that throughout South Los Angeles where all we did was bring in access to multi-national corporations so that our wealth could be extracted a little easier. Below living wage jobs were offered to folks, but we didn’t really empower the community.”

Goodman believes in an alternative economic development model called community wealth building.

“Where the community improvements are really for the community, not just to allow people to exploit our assets,” he said. “That means that there has to be shared ownership, community ownership, democratic processes, tools and tactics at play where the goal isn’t just to create more Black millionaires for a fortunate few, but spreading the wealth to the masses of Black people who are in our community who are low income.”

Many Black residents in South Los Angeles fear that they will be pushed out of their communities because of the increasing costs of housing, but Goodman is telling people that it is possible for them to stay in their neighborhoods.

“There is a way in which we get to see the housing that we can afford, and not the unaffordable luxury housing that’s being built,” he said. “The improved retail environment that we want. The improved office space so that we can cultivate businesses that feed this community with economic opportunity. But it requires us to be far more radical.”

This past April, Goodmon participated in the National Emergency Summit on Gentrification in Newark, New Jersey. The summit brought together housing justice leaders, elected officials and civil rights organizations from around the nation. One of the most common issues that the attendees all dealt with was accountability from Black elected officials.

“Leaders from D.C., Atlanta, New York, L.A., and the Bay area, we were all saying that we’re being let down by our local Black elected officials,” Goodmon said. “They’re not just being not supportive. They’re greasing the wheels of gentrification in our communities.”

Goodmon met New York State Assemblymember Charles Barron, who presides over a district on the east side of Brooklyn. His wife Inez Barron is a New York City Councilmember, who’s district presides over the same area.

“He says he’s proudly a Black radical politician,” Goodmon said. “He has been able to lead the only community in hyper-gentrified New York that has seen a massive increase in Black population and a decrease in White population. He’s seen a thirteen percent increase in Black population and six percent decrease in White population in East New York. This is while Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant have well over 200 to 600 percent increases in White populations and drastic decreases in Black population. Fifteen percent and a lot more than that in some cases. He’s seen an increase in Black population in East New York because he says, ‘I don’t let anybody build projects that people in my community can’t afford.’ He said, ‘I don’t allow market-rate development because my community can’t afford it. And when it comes to the affordable housing that they have to build, we’re not going to let them do it based on the county’s area medium income, which is much higher than our local community. We’re going to make them do it based on what we can afford.’”

While many people who are angered by gentrification typically oppose new development, new projects are welcomed in Barron’s district.

“He is seeing development take place,” Goodmon said. “But it’s development for his people. We’re using that as a rallying cry here in L.A. ‘If we can’t afford it, don’t build it.’ Why are we allowing a South Los Angeles community, the Black L.A. community, why are we allowing this community, where no zip code has a medium income for a household of four that is above $44,000. Why are we allowing market-rate development that requires you to make $120,000? We are by definition inviting gentrification. So just put up the guard rails. Only three percent of the people in our community can afford market-rate. This development is not for the people; it’s meant to displace the community.”

One of the goals of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition is to get locals involved in the political process, and to hold elected officials accountable for the developments that they green light.

“If you don’t like a development being built in your community in the city of Los Angeles, you have one person to speak to,” Goodmon said. “That’s your city council member. They are the 15 kings and queens when it comes to deciding whether things are built in the community. So you have a responsibility as a citizen, as an institution, as an organization, who cares about this mostly Black Crenshaw community, staying an affordable space for the community. You have a responsibility to call them out so that they will do what’s right.”

Goodmon said that most of the donations in the race to replace County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who is termed out, are coming from donors who live outside of the district. Goodmon points out that people within the district have sway in the election. For candidates to have legitimacy, they have to obtain endorsements from local preachers, heads of community-based groups, non-profit organizations, unions, local democrat clubs, and be invited to community forums.

“The people who participate at these multiple civic levels have influence over all of that,” Goodmon said. “They’re members of unions. They go to churches whose pastors are influencers. They’re contributors to non-profits. They’re members of democratic clubs.

“Until we as a community say that we want there to be a Black part of Los Angeles; that there will be Black people in L.A.; that we are not going to go the way of San Francisco, where famously a movie came out called, “The Last Black Man in San Francisco,” which I think is accurate,” Goodmon said. “Until we take that on as our task and say, ‘No, you’re doing wrong, you’re going to get right or get out,’ and make demand of our institutions and our leaders on the ground, I think it’s fantasy to expect those that are in positions of elected office, that they’re going to adapt.”

Over the course of the Summer of Resistance Town Halls on Gentrification, over 250 people attended the workshops and 67 people signed up for committees. While there were discussions on the various aspects of gentrification, the Crenshaw Subway Coalition isn’t just about talk, but they are also seeing results.

“We saw a presentation of an anti-displacement zone from (Los Angeles City Council President) Herb Wesson,” Goodmon said. “We saw (Councilmember) Marqueece Harris-Dawson stand up and say that he does not support the Dorset Village Project which is supposed to wipe out 206 families in rent controlled units to bring in over 700 units of luxury housing. We saw movement on that.”

One of the issues with the Dorset Village Project (Slauson Avenue and 10th Avenue) was that the majority of the units were going to be at market rate, which prices out most of the people who live in that area.

“Even in a place like Baldwin Village, you’re seeing rents drastically increase even though it has rent control because of vacancy decontrol. Basically when a person moves out, the owner of the building can raise the rent to whatever they want. So we’re seeing older buildings that were built in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, but don’t have the amenities that you see on the westside, in a Baldwin Village, the “Jungles,” community, that used to be the place if you were a security officer, grocery worker, a school bus operator; these low-income jobs that many of us have. We would pay about $900 for a two bedroom apartment. Those are now going for $2,400. And the market will only get higher. When you think about all the new development that’s coming, you’re looking at somewhere from 3,500 to 4,000 market-rate units being brought on Crenshaw between just between Slauson and Adams. Then you bring in the high-end paying jobs that are coming along the La Cienega corridor. You can see how in five years from now, $3,500 for a two bedroom will be the normal. Now they’re bringing in tech companies. We’re going to see an influx of people who don’t look like us, who make six-figure incomes, and that’s jacking up the (housing) rate. If this is going to be a community where all of the apartments went for $2,400 and homes went for $900,000, this will not be a Black community.”

Goodmon said that when people hear “market rate,” they should hear, “not for me.”

“Right now in the Crenshaw community, over 70 percent of the Black renters spend more than 30 percent of their income, and almost half of those renters spend more than 50 percent of their income on rent,” he said. “The bulk of this community, as it is with most Black communities in America, are renters.”

Home ownership is also a major issue, as many Black people who live in South Los Angeles are being priced out there too.

“We’re not competing with each other anymore,” Goodmon said. “When there is a house for sale in Leimert Park, it used to be, I was competing with you. We would both be putting in our bids. But now you and I are competing with flippers. People who come in, buy the house for $670,000. Maybe they put $100,000 in it to turn the garage into a granny flat, and then they put it on the market for $1.1 million. How are we supposed to compete with that? How am I supposed to compete with somebody who can come in and provide a cash offer to buy a home for $670,000?”

Heading into the fall, the Crenshaw Subway Coalition will continue to meet. They’ve formed committees for land use oversight, wealth building, and a committee to maintain the Umoja Center.

“We’re going to look at creative ways in which we are able to use the assets in our community to benefit our community; not displace our community,” Goodmon said. “We’re going to put up a fight against those projects and those polices that attempt to put us out. We’re not going anywhere. I’ll be the last Black man in Leimert Park. I’m not going without a fight.”

The Umoja Center is located at 3347 W. 43rd Street. Find out more information about the Crenshaw Subway Coalition at www.Crenshawsubway.org and follow them on Facebook.