Reparation presentations are taking place at local community meetings.

By Jason Lewis

In 2021, California’s state legislature became the first state in the nation to create a task force to study reparations. Since the creation of the California Reparations Task Force, the city of Los Angeles has followed suit in creating the City of Los Angeles Reparations Advisory Commission. These studies were highlighted at the recent State of Black Los Angeles, which discussed issues that impact Black people in the city and county of Los Angeles.

This discussion also took place at a recent Empowerment Congress West Area Neighborhood Development Council meeting, which covers Baldwin Hills, Leimert Park, and Crenshaw areas. At the meeting, City Commissioners Michael A. Lawson and Mandla Kayise, and state task force member Reggie Jones-Sawyer spoke about the reasoning for reparations and the work that their groups have done.

“Black Angelenos are in a unique position relative to the rest of the country because we’re one of the few cities that has both a California state reparations task force and Los Angeles city reparations advisory commission, so we’re one of the few populations that has two bodies to engage the reparations discussion,” Kayise said. “What we would like to see is that our community fully embrace this reparations discussion and become leaders in it.”

The city advisory commission has been giving presentations at community meetings and churches, and they have held several virtual meetings that are open to the public. Earlier this year, this pilot program launched the study of the Black Experience in Los Angeles in partnership with California State University, Northridge.

“We’re studying and looking at what harms have impacted African Americans across the city of Los Angeles and throughout the history of Los Angeles,” Kayise said.

Detractors of these local studies have pointed out that California was not a slave state, which these groups have acknowledged.

“It’s important to say that while California was not a slave holding state, it was a participant in the process of slavery and the enforcement of slavery,” Kayise said. “There were people who were captured and returned to slavery from here in California. Racial terror we know extended across the country. Political disenfranchisement. All of those harms are harms that have occurred across the country, certainly have their own experiences in the state of California and in the city of Los Angeles.”

The city advisory commission looks to submit their recommendations to the Mayor’s Office in line with the January 2025 budget deliberations cycle so that the city can discuss how to fund it.

On the state level, the reparations Task Force created a 1,100-page report that was released to California legislators and the governor.

“This is about harms; it’s not about race,” Jones-Sawyer said. “It’s about harms to a group of people. This is like we’re doing a civil lawsuit against the state of California for what they did to African Americans in the state of California for centuries.

“Now comes what I believe is the hard part, which is to turn that into legislative and budgetary documents so that we can get it approved next year in the budget.”

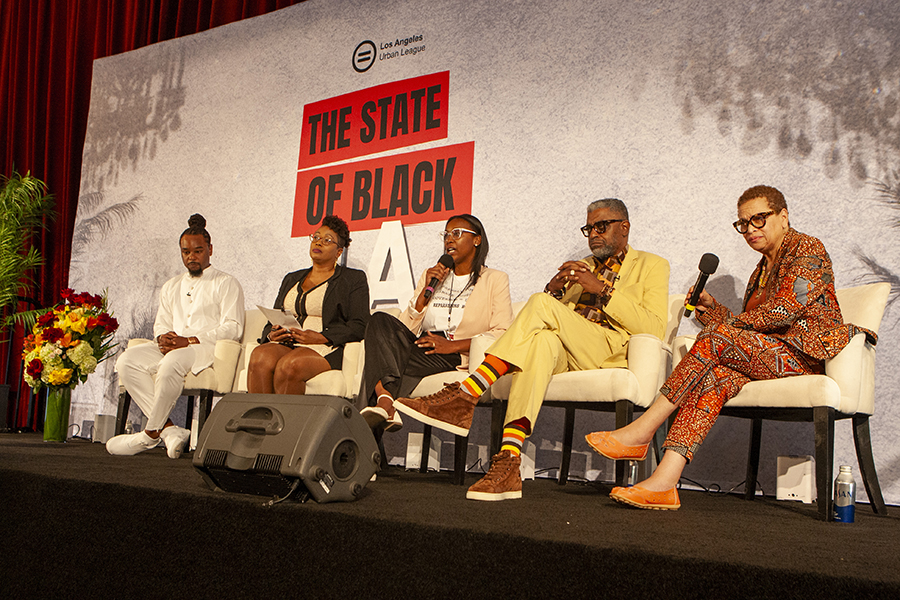

At the Urban League’s State of Black LA Summit, there was a panel discussion which featured Marcus Hunter, African American studies professor at UCLA; Kamilah Moore, Chair of the California Reparations Task Force; Khansa Jones-Muhammad, vice chair, City of Los Angeles Reparations Advisory Commission; Anthony Samad, executive director of Dymally African American Political and Economic Institute, Cal State Dominguez Hills; and Julianne Malveaux, dean of College of Ethnic Studies at California State University, Los Angeles.

Malveaux is writing a book titled “Lynching, the Wealth Gap, and Reparations,”

“What lynching did to our people is frightened us,” Malveaux said. “A man was lynched for spitting on the sidewalk. A man was lynched because he did not call a White man ‘Mr.’ Lynching was basically an instrument of fear. And that, in my mind as an economist, suppressed the Black ability to accumulate, to thrive, and in some cases even when we did thrive, sundown towns, and they had them in California, ran us out. So when you hear the home ownership data, and the fact that we own fewer homes here in L.A. County now than before restrictive covenants. Reparations is a way of repairing, restoring, bringing back and making us whole.”

For reparations to pass in California on a state level, 41 assembly members, 21 senators, and the governor has to sign the bill.

Many detractors of reparations say that slavery happened a long time ago, but proponents point out that reparations is also about the 100 years after the end of the slavery through the Civil Rights era. Black people were treated as second class citizens and were not permitted to participate in government-funded wealth building programs.

“The justification for reparations in the state of California, yes enslavement is important and that’s the foundation for the claim so to speak,” Moore said. “There was slavery in the state of California. But the true crux and justification for reparations in the state of California and national is for that broken promise of reconstruction in this country that only lasted seven years due to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. And these lingering incidents of slavery that has manifested in exclusionary public policy in various areas of life as it pertains to African Americans. It’s about slavery, but it’s also about addressing the legacy of slavery. Addressing and eradicating those lingering badges and effects of slavery that still persists in this society and are weaponized disproportionately against descendants of slaves.”

Many detractors seem to believe that reparations will be paid out of the pockets of the American people, but that is not the case.

“I’m not talking about your grandmother paying my bills; paying me reparations,” Hunter said. “I’m talking about the U.S. federal government. I am talking about the California government. I am talking about Alabama state government. We are talking about governments in a state of repair.”

These reparation studies are making a direct link to slavery and segregation as to why Black people have poor rankings when it comes to economics and health.

“If we want to know why Black people make $40,000 less in L.A. County than White people, and $20,000 less than everybody in the aggregate, it’s because of economic subjugation,” Samad said. “Economic subjugation simply explained as this: they hire us last, they fire us first, they pay us less, they charge us more, they work us harder, so we die sooner. All of the outcomes in the report indicate that there is a compounded effect of racism. It’s not from one single source. It’s multifaceted.”

To stay updated on the progress of these studies, visit www.californiareparations.info and www.blackexperiencela.com