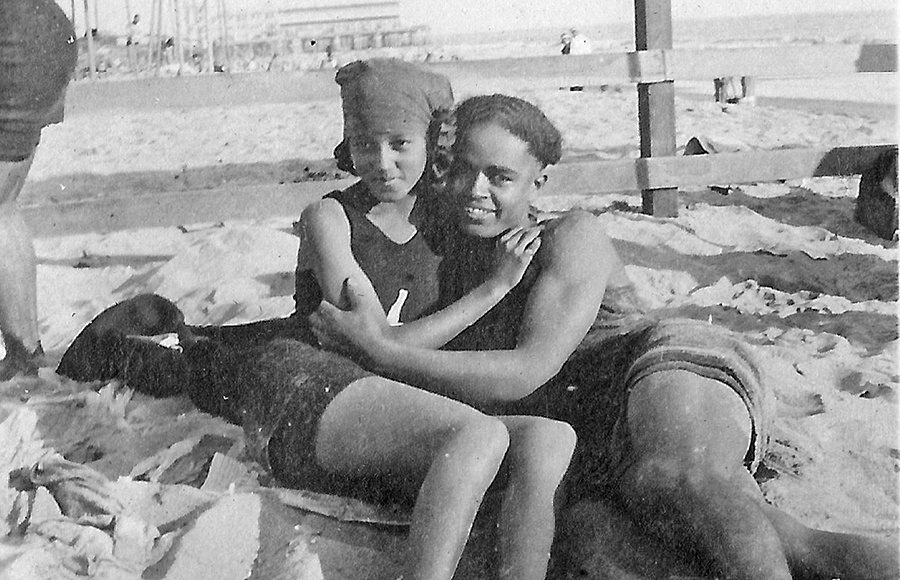

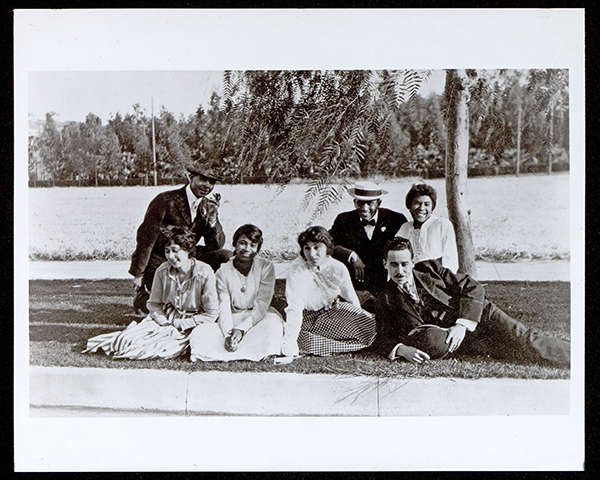

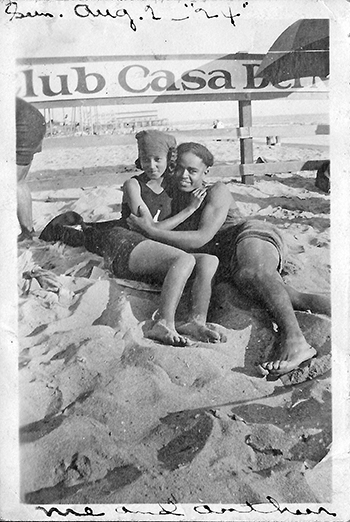

Historian and author Alison Rose Jefferson showcases photographs from her book “Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era” at the California African American Museum.

By Jason Lewis

Black Americans began to migrate to Los Angeles during the 1890s to escape the racial violence and racism of the South. The first half of the 1900s saw two great migrations as Black people were seeking the California dream. However, when they arrived here they were met with racism and segregation. But they were able to fight for access to public places such as beaches, parks, and public swimming pools. They fought for the right to enjoy the California dream.

Historian Alison Rose Jefferson captured this era in her book, “Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era.” The work from her book is the basis for an exhibit at the California African American Museum (CAAM). “Black California Dreamin’: Claiming Space at America’s Leisure Frontier,” runs from August 5, 2023 to August 18, 2024.

“It’s a narrative about African American experiences here in Southern California that revolve around our experiences in the outdoors and developing places of leisure at various beaches and inland areas around Southern California,” Jefferson said. “In addition to these experiences of African Americans developing pursuits of leisure, outdoor beach and inland places, it’s also a story of business development, community development, and migration patterns. When these places were being formed, many of these people were first generation Californians coming here. They moved here for new life opportunities for the outdoors; for the freedoms that California had to offer.”

While Southern California offered a better life for Black people than the South did, Black people still had to fight against racism.

“There was discrimination all over the United States as it relates to Black people,” Jefferson said. “The reason why people in Los Angeles feel that it wasn’t as bad is because it wasn’t as obvious as it was in other places around the country, particularly the South. And because we had civil rights laws in the state of California, Black people fought the discrimination that occurred. As it relates to our living conditions, the Black codes weren’t on the books segregating you, but you did have issues of redlining. Early in the 20th century you had the racially restrictive covenants that were put on properties that kept Black people from buying or living in certain areas. Then you had the informal kinds of discrimination that occurred where a real estate agent wouldn’t allow you to get access to the property to buy or rent. And then later in the 20th century you get the redlining with the loans. You couldn’t participate in some of the government loan programs.

“Black folks did have problems here, but they were able fight them. And the White people weren’t as vicious and evil as they were down in the South. The discrimination here was not consistently meted out. You might go one day to Jenny’s store, and Jenny serves you. And then you go to Jenny’s store two days later and Burt is at the counter. And he’s like, ‘Don’t come in my store.’ So it was not uniform in term of how discrimination happened to Black folks here.”

Because of the restrictive covenants, many Black people were forced to live in the Central Avenue area, but that did not prevent them from branching out to some degree in other areas of the city and county.

“We were all over Southern California, but when you start talking about community in the early parts of the 20th century, and the bigger business development, that was in the Central Avenue community,” Jefferson said. “These leisure sight areas that I cover in my book were places that African Americans were developing outside of Central Avenue. But they were still living in Los Angeles. In Manhattan Beach, the Bruces, who started their resort in 1912, they lived on Santa Fe in Los Angeles. In terms of Lake Elsinore, many of the (Black) people who were developing resorts there didn’t live there either. They lived in Los Angeles.”

In Southern California, Black people had a lot more access to aquatic activities than in the South. For a short period of time Black people were unable to use public swimming pools, but they were able to fight for equal access. And they were able to find spaces at the beach.

“The beaches weren’t segregated; not in the formal sense of the word,” Jefferson said. “We had laws in California that said that the beaches were a public resource and was open to everybody. Now sometimes those laws were not enforced, and sometime people did try to use subterfuge measures to say that it was private beach. That happened in Manhattan Beach at one point. But you could use the beach wherever you wanted to. Now whether you wanted to was another story because you might be harassed. So it has to do with how secure you felt as an individual and with what your rights were. And also, do you have backup? Because it might be one day at the beach and you know your rights, but it’s a bunch of White boys with some clubs and a gun. So what are you going to do?”

The Inkwell in Santa Monica, just south of Pico Boulevard, was a popular meeting place for Black people because it was easy to get to by public transportation, and because there was a historical African American community in Santa Monica.

“There was safety in numbers there,” Jefferson said.

At the CAAM exhibit, people will be able to view a wide range of vintage photographs and artifacts from the early to mid 1900s. In the photographs, people will be able to see Black people living the California dream.

“They’re claiming space,” Jefferson said. “Showing a new identity for Black people because people never think of Black people as enjoying the outdoors, or being recognized as being a part of the California Dream. These are photographs recognizing Black people in that light. They are claiming space in leisure and for them to enjoy themselves was a part of the battle for reshaping the American identity, and it was a part of the battle in fighting for social and political rights in the United States.”

For more information on the CAAM exhibit, visit www.caamuseum.org. Jefferson can be followed on social media and visit her website at www.alisonrosejefferson.com to purchase her book.