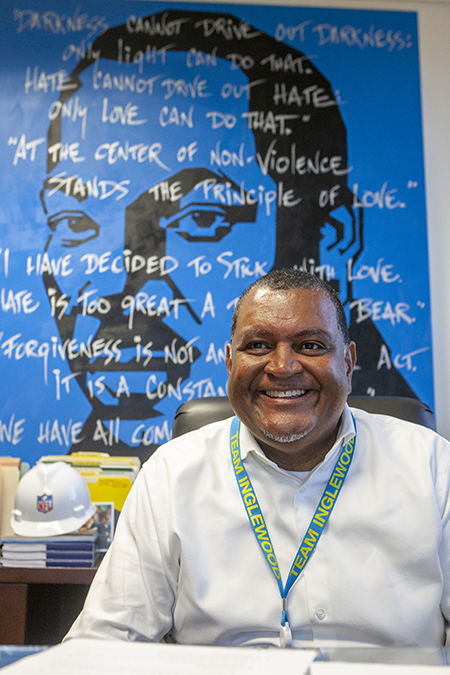

Wise decisions led Jackson from the Nickerson Gardens housing projects to becoming an urban planner in Inglewood.

By Jason Lewis

Inglewood’s plans to revitalize Hollywood Park have been very bold. So bold that they landed two NFL teams who will play in a brand new state-of-the-art stadium. The complex will feature restaurants, retail shops, a hotel, movie theaters, office space, and housing. This sports and entertainment complex will rival anything of its kind in the nation.

These bold plans are a part of Inglewood Mayor James T. Butts’ vision, and they all went across Inglewood’s Economic and Community Development Director Christopher E. Jackson Sr.’s desk for approval.

Jackson has a very exciting career as an urban planner. He’s one of the movers and shakers when key decisions are made that will impact a city, and he was right there in the mix when Inglewood was in competition with neighboring cities to land an NFL team. After AEG’s plan to build a stadium in downtown Los Angeles fell through, Inglewood was one of the front runners to bring the NFL back to this area.

“We were battling with Carson, and that was fun,” Jackson said. “We had the Rams on one side, and the Chargers and Raiders on the other side. It’s amazing how it all worked out for everybody.”

Jackson has to interact with a number of high-profile people and moving parts to make these deals happen. He has been with the city of Inglewood for 11 years, and he was a part of the original Hollywood Park plan, which did not include an NFL stadium.

“I ushered in approved plans for that, and then it was all scrapped when (Rams owner) Stan Kroenke showed up,” Jackson said.

When Kroenke decided to move the Rams from St. Louis to the Los Angeles area, all of the plans dramatically changed and Jackson had to quickly move the the Hollywood Park project in a different direction. Jackson’s decision making skills were put to the test, just as they were when he was growing up in the Nickerson Gardens Housing Projects in Watts. Choosing the right paths led him away from gangs and toward college and a professional career.

“Life was difficult from the standpoint of having sufficient things for a childhood,” he said. “It was an environment at that time during the ‘70s when gangs weren’t what they became to be in the ‘80s with crack and other drugs, but it was still territorial. There were pressures to become a part of a gang.”

As a young teenager, Jackson had a close friend who joined the Baby Bounty Hunters, which was sort of a feeder gang into the Bounty Hunters, a Bloods gang in Watts.

“My mom just fought it,” he said. “She just told him no. She wasn’t going to let me go that route. That made a huge difference in the direction that my life went.”

While Jackson grew up in a rough environment, there were positive aspects of his community that he enjoyed, and he was able to learn valuable lessons from the negative aspects.

“I had friends and we rode bikes,” he said. “I had a assemblage of a childhood that I relish. I look back and it helped form me. A lot of my cautionary tales comes from growing up in the projects, and being aware of circumstances. Questioning things and not always getting on the boat and going off. But actually questioning why. That’s played very well for me in my career, because you have to ask those questions.”

After attending 112th Street Elementary School, Jackson’s mother sent him out to the San Fernando Valley for middle school and high school opposed to sending him to Markham Middle School and Locke High School.

“Living in the projects, it was dangerous to get to Markham,” he said. “I would of had to go through gangs to get there. My mom knew that wasn’t going to be good for me. I probably would have been in a gang just to protect myself, or I would have been a casualty like a lot of my friends were unfortunately.”

Jackson was able to see a different and more enjoyable way of life while spending most of his time during the week out in the Valley.

“That was a pivotal moment in my life, because I got to see the dichotomy of two types of existence,” he said. “I had my home in Watts. We had Will Rogers Park, which is Ted Watkins Park now. I remember at the park, the pigeons were afraid of you. There were no squirrels. It was kind of an eerie environment, but you figure out how to enjoy it. And then I go out to the Reseda area where Sequoia Jr. High School was, and at the park they’re playing games, the ducks are coming up to you. Guys were walking around with no shoes on because there was no glass on the ground. You would never do that in the projects because you’d cut your feet up.”

Jackson was at a crossroads in life at a very early age.

“Do I want the environment that I was growing up in, or do I want to have an opportunity to have the environment that I was experiencing out in the valley,” he said. “They had nice homes and nice cars, but then I was getting back on the bus and coming home to craziness.”

While attending Reseda High School, Jackson took classes in the industrial arts program, which included drafting and architecture classes. He competed in the NAACP’s Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics (ACT-SO) and the National Association of Women in Construction competition. From there he was accepted at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He had plans to become an architect until he had a conversation with a senior at the school who asked him if he had ever heard of urban planning.

“He said that architects draft up stuff, and landscape architects draft up stuff,” Jackson said. “They have to give it to these people called urban planners who work for cities, and they approve it according to the standards that they set.”

Jackson went on to earn a degree in Urban and Regional Planning, and obtained his first full-time job as an urban planner in the city of San Dimas while he was still in college. He went on to work for municipal governments throughout Southern California in such cities as San Dimas, Tustin, Whittier, Santa Clarita and Los Angeles. Landing a job in the city of Inglewood allowed Jackson to work with and around people who looked like him.

“I knew that working in Inglewood was going to be totally different from anywhere else that I worked,” he said. “It’s a Black and Latino city with African American and Latino leadership. In other cities, I was always the minority guy. So coming here was refreshing, and I have enjoyed it.”

When Jackson was bussed out to the Valley, he was able to see a different and better way of life. But that was mostly around White people. With his success and ability to make change, he is recreating that way of life in Inglewood while living in a Black community.

“Living in Inglewood is unbelievable,” he said.

Outside of Jackson’s career, he is an ordained minister at Mt. Sinai Missionary Baptist Church.

“I have a morality compass that stems from the Word of God,” he said.

Jackson is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. He was initiatd through Iota Psi Chapter at Cal Poly Pomona and he is currently a member of Beta Psi Lambda Alumni Chapter, where he is a past chapter president.

“Being a past president of Beta Psi Lambda Chapter helped propel me to where I’m at right now. The Brotherhood will test you, and that’s what they’re supposed to do. And sometimes they’ll test you by fire.”

Jackson is also a member of the Planning in the Black Community Division (PBCD) of the American Planning Association.