The LAPD has made connections with certain demographics, but there is still a disconnect.

By Jason Lewis

The racial climate in America has always been strained to some degree, and it has reached a boiling point over the past few years, as movements such as Black Lives Matter and community-based organizations throughout the nation have staged protests against unfair treatment of black people by law enforcement.

There have been trust issues between black communities and the law enforcement agencies that serve them. Those issues partly stem from a disconnect that has led to an ‘us versus them’ mentality on both sides, and the city of Los Angeles has not been able to avoid those issues.

The LAPD has made efforts to connect with the community through various programs, and there has been success with older people (over 50), preteens and teenagers, but the disconnect remains with young and middle-aged adults, which tend to be the age groups of the people who have issues with law enforcement, and the people who attend protests.

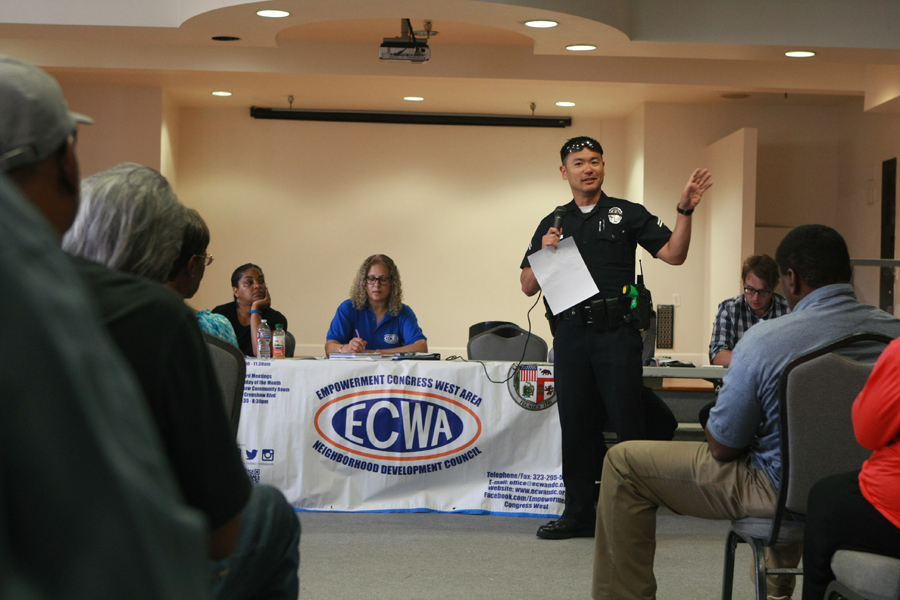

In the LAPD’s Southwest Division, Senior Lead Officer Sunny Sasajima has spent the last eight years building relationships with community members in the Crenshaw area. He attends various neighborhood council, block club, and stakeholder meetings, where he reports on the police department’s activities, as well as gives crime reports. One of his goals is to create a bond with the people that he serves.

“I think as a whole, we need to establish that from both sides,” Sasajima said. “From a police standpoint, being able to, not so much punch in and punch out for the day, but while we’re here, kind of get the opportunity to embed ourselves into the community, and similarly folks in the community feeling comfortable to interact with the police.”

Communication helps Sasajima and other officers gain the confidence of the community members that they have formed relationships with.

“I think that there has to be an ongoing dialogue,” Sasajima said. “Not just when something happens, or not in the aftermath of a controversy. The dialogue has to be there when things are good and when things are bad. The dialogue has to be a constant.”

Sasajima welcomes the communication with people who may not want to form a bond with a police officer. He recalled an interaction at a recent march against police brutality, where a black man with his three children had a conversation with him, even though some of the other protesters urged the black man not to talk to the officer. The man was upset over the issues, but he wanted his sons to see that it is okay to talk to a police officer.

“I think that he saw it with a much more wider perspective,” Sasajima said. “It can be one way where it’s us versus them, kind of furthering that rift, or we can bridge that gap. If there is somebody willing to talk to me, I have to be willing to talk to them and meet them in the middle. Even with everything that’s going on.”

Each LAPD division has a Community-Police Advisory Board (C-PAB), where local residents meet with senior officers of that area on the first Monday of each month. The Southwest division meets at the Los Angeles Child Guidance Clinic, across the street from USC. At this meeting, people can voice their concerns, and also work with LAPD officers to solve issues. The senior command and senior lead officers are required to attend these meetings.

There is also a teen C-PAB that meets twice a month. Once at the police station, and once at the office of the Los Angeles Sentinel.

The C-PAB was created after the 1992 Los Angeles Riots as a way to better connect the police department with the community.

“The powers that be agreed and understood that the Los Angeles Police Department needed to figure out some ways to better and more effectively interact with the community,” said Johnnie Raines III, a long time community activist and C-PAB co-chair.

“It may not always be friendly, but the dialogue takes place,” Raines said. “And there are some things that grow out of that. One group (of community members) was adamant about something that they wanted, and now they have the person who is the boss of all of the senior lead officers talking to them at the direction of the captain. And that’s what works.”

Raines points out that this committee is a partnership between the LAPD and the community.

“This isn’t set up as a place that as a community member that you come and drop off a problem,” Raines said. “If you’re really sincere about fixing something, you need to be willing to put in some sweat equity.”

When there are concerns, ad hoc committees that are mixed with officers and community members are formed, and they work together until the issue is resolved. Raines does not put the full workload on the police department to solve problems, and encourages involvement from the community.

“When people tell me that they have a gripe, concern or issue, I tell them when the meeting is,” Raines said. “If they don’t show and I see them again, they ask me about the problem, I tell them, ‘I told you where to bring it. You chose not to bring it so I figured it must have been solved.’”

But one major issue with this committee, similar to the neighborhood council, stakeholders, and block club meetings, is that there are not many people under 50 who attend, and many of the participants are senior citizens.

Older people have dramatically different issues than younger people. Some of the concerns that were mentioned at the last C-PAB meeting were the use of illegal fireworks, and cars parked illegally on residential streets. Those typically are not issues that younger people are concerned about.

“I would love to see younger people participate in this,” Sasajima said. “In a forum like that, when you are afforded an audience with all of the senior lead officers, you’re afforded an audience with the captain. You have the opportunity to speak directly with the command staff, the guys who make the decisions at these divisional levels. People should capitalize on that.

“The age group that we need to be outreaching to, the ones that we need to have that dialogue with, we’re not reaching that one,” Sasajima continued.

While younger people do not attend these community meetings, they are bringing national attention to the issue of police brutality against black people. Their peaceful protests, marches, and demonstrations are attracting a lot more people than the community meetings.

Misty Wilks is a long time community activist who understands how the younger and older demographics go about making change. She staged her first walkout over teachers’ salaries back in the mid 1980s, when she was only 13 years old.

“You’re young, you’re idealistic, you feel like if you make some noise, that’s how you make change,” Wilks said. “So you send out your rally cry, and 20 people show up. If it’s good, 100 people show up. And then momentum dies down and you realize that you spent all that energy. And what actually changed? I think that what happens, or at least what happened for me, it became the older you get the more aware you are to actually affect change.”

While Wilks is still in touch with the younger generations’ methods of protest, she sees the value of the way that older people bring about change.

“You have less and less time to devote to the cause, so what’s the thing that’s probably going to make change? If I run down to Leimert Park for a protest, can I make as much change as if I call (Supervisor) Mark Ridley-Thomas and say ‘look, what is going to be the most effective?’ The older and older I get, and the less time I have, I much rather do the thing as an older adult that will effect the most change the quickest. Which may mean attend a meeting and rallying these people.

“We can get the mayor and the chief of police to a meeting,” Wilks continued. “I can get them on tape, or get them in a room of people and get them to make promises, or get them to form a committee to research something. Change may not happen immediately, but it’s an effective way to make change in the institution at the same time that the protests are going on in the street.”

While the methods to bring change are dramatically different, it appears that both approaches are greatly needed.

“I don’t think that it’s one or the other,” Wilks said. “I think it’s both things together. I think you have to have the two. You have to have the people who are protesting to underline those of us who are engaging on a different level. Like, ‘look (politicians), you see those people (protesters) in the park, you better take care of this issue.’

“No matter how explosive our meetings get, it’s not going to make global news,” Wilks continued. “When you start tearing something up, that’s what makes worldwide news. So you need both. You need protesting in the streets, and you need people protesting in the meeting. What they’re doing in the street lets the politicians know that what I’m telling them in the meeting is serious. They need to handle this (the issue) so that they can get that (protesters) under control.”

While the LAPD has made a connection with older people, there is still a major disconnect with the younger protesters, and there might not be much dialogue between the two sides.

“To my knowledge, I have not seen any evidence of positive, or an attempt at positive interaction,” Raines said. “Does that mean that there is none? No. That just means that I have seen none.”

At a recent Los Angeles Police Commission meeting, where the recent officer involved shootings of black people was a heated topic, leaders of Black Lives Matter and Los Angeles Community Action Network (LA Can) spoke about not being able to engage LAPD officials or the Police Commissioners.

“We tried to set up a meeting with (president of the Police Commission) Matthew Johnson,” Said Eddie H of LA Can. “Our organization, as well as Black Lives Matter. We had a tentative date. He came back and said that he was unable to meet on that date. We tried to get another date with him, but every time he came back with excuses. He basically threw the issues that we wanted to speak to him about to the side. He gave us parameters by which he would have a meeting with us, and he came back and he nullified that as well.”

Also at that meeting, Melina Abdullah, a prominent member of Black Lives Matter, took issue with Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and Police Chief Charlie Beck meeting with rappers Snoop Dogg and The Game, but not inviting protesters to the discussion.

“No matter what you say about wanting to have conversation, you only want fake contrived conversations,” Abdullah said to Beck. “You don’t want to deliver the kind of transformation that we need to have real, safe communities.”

While the LAPD has made positive connections with certain demographics, and those relationships have appeared to have resolved certain issues, there is still a disconnect with younger members of the community who are trying to bring about change.